TRANSCENDENTAL MONISM

The beautiful presentation of the higher form of the Sufi philosophy given by Mohammed Barakatullah in recent numbers of Mind, with which the writer finds himself remarkably in accord, has moved him to submit to its readers a rough summary of his own as yet unpublished philosophical system (the manuscript of which passed through the hands of a well-known scholar on the Atlantic slope several weeks before the first of the Sufi articles appeared), by way of a document illustrative of the measure of agreement which may often be found among thinkers representing the very religions and philosophies which, in their superficial aspects, are most diverse and contradictory.

The agreement derives much of its significance in this case from the fact that the present writer is an Ultramontane Catholic, who believes himself to represent the pure Albertino-Thomistic Scholasticism of the Dominican school (as opposed to the voluntarist or ultra-realistic Scholasticism of the Scotists, the skeptical Scholasticism of the Occamites, the Suaresianism of the Jesuits, and the Ultra-Aristotelianism of the typical Neo-Scholastics), which he has developed (in the light of modern and Oriental philosophy and science, and yet from within, and not by any mere process of accretion or eclecticism) without contradicting.

The New Thought, with many, at least, of the contentions of which both the system herein described and that outlined by Barakatullah will be recognized as in close agreement, implies a continuity in the unfolding of the spiritual through the material, and the manifestation of the Divine through the human, which is sometimes lost sight of by those who are more vividly conscious of the novelty than of the eternity of the principles they set forth.

The turning inward and upward of the individual human soul should not be disassociated from the corresponding movement of humanity at large, the record of which constitutes the higher spiritual history of the world.

The New Thought is new in contrast to the materialism and empiricism of the immediate past; but there was a time when that was the “new thought,” and it was no better and no worse for being so.

The movement of human progress, like biological evolution, has many countercurrents, which it is only natural for those who are floating in them to mistake for the main stream. The Zeitgeist changes from day to day; that which was old becomes new, and that which was new becomes old; but the Ewigheitgeist sets forth unchangingly the Goodness and Beauty and Truth that is ever ancient yet ever new.

Not a link is missing in the Golden Pythagorean Chain, even since the days of Proclus and Synesius. In every generation since the time of the Orphic bards (who inherited the shadowy glories of the Age of the Gods, when Apollo is fabled to have founded the Delphian Oracle and Dionysus to have made his grand triumphal march, as the prophet of the Great Mother, through all the countries between India and Thrace), there have been Teachers (who may be reckoned by name, without a break, at least from the days of Pherecydes the Master of Pythagoras) who firmly maintained the supremacy of spirit, the nothingness of the universe considered apart from Him of Whom it is the manifestation and the symbol, and the privilege and duty of man to aspire to conscious union with the Absolute Being.

Swedenborg’s doctrine (which was that of Aquinas before him) of the Three Discrete Planes—matter, spirit and God—applies, not only to the Macrocosm and to the individual, but also to those social organisms called religions.

The “clothes of religion,” the formulae, ceremonials, laws and other externalities in which all the more ancient historic religions so abound, should not hide from us, but rather reveal to us, the inner spiritual truths, and even Divine Realities, of which they are in every case, though in different measure, the correspondences, symbols and instruments.

Even he who believes that religion is, in its very nature, essentially one, interiorly and therefore, by the law of correspondences, exteriorly, may recognize that no religion can exist that does not derive its vitality from the elements of truths and goodness present in it; and still more should those representatives of the spiritual and idealistic worldview who repudiate all organized religions feel themselves obliged, for consistency’s sake, to seek for the Spirit, the Idea, of which each of them must (since all the visible springs from the Invisible) be the embodiment; and it should not surprise them to find that this Idea, especially in the case of the religions of longest duration and widest influence, is harmonious with the Thought which is eternally New.

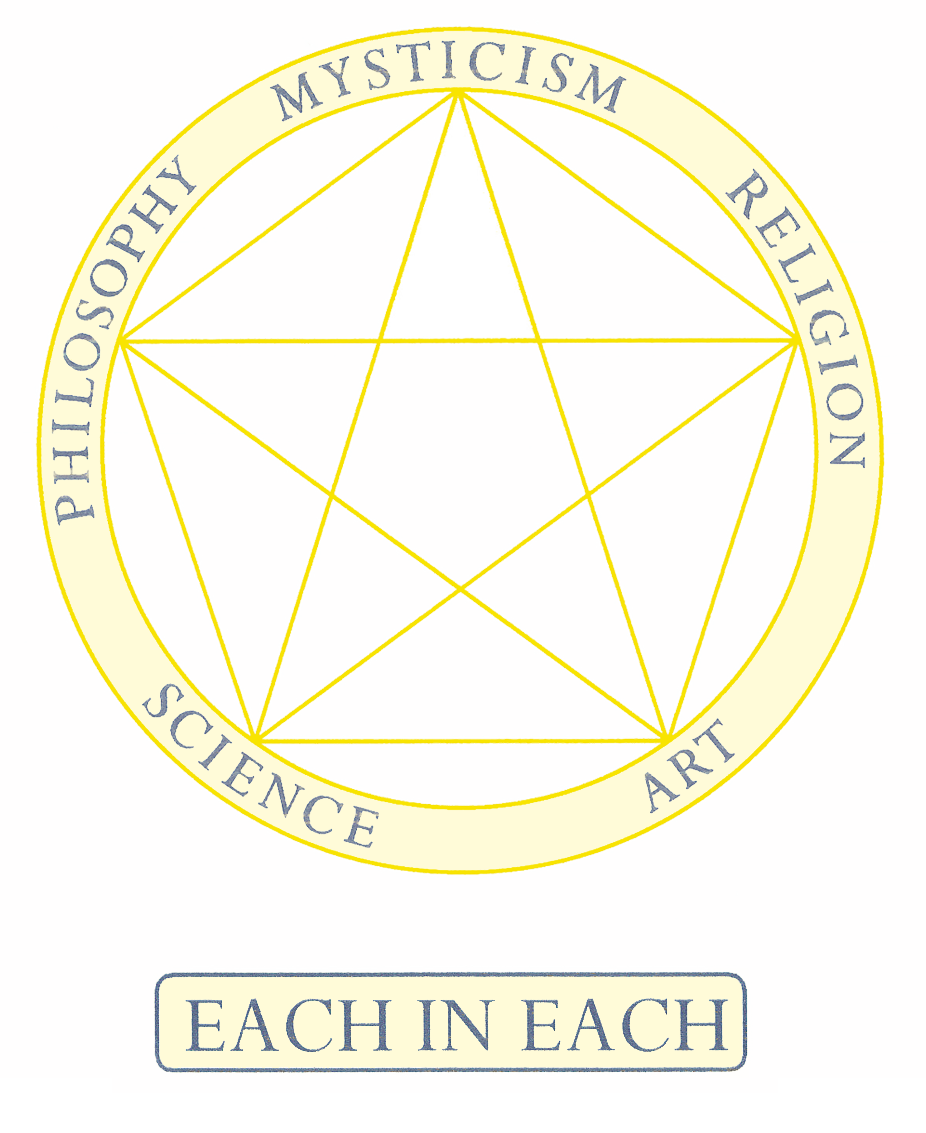

Transcendental Monism is based upon the principle of the essential inerrancy of the human intellect, and the derived principle (recognized, but improperly applied, by Menedamus of Eretria and in modern times by Cousin) of the truth of the positive and constructive side of all philosophies, which thus supplement each other. Yet, it is by no means either an eclectic, or a mere syncretic, system.

Philosophy is not an art but a science; the art of philosophizing represents the inchoate stages of the Absolute Philosophy in the process of its construction or discovery; and each so-called philosophy is, therefore, generally speaking, trustworthy in the special field (part or aspect of truth) with which it has dealt.

All philosophical methods, whether objective or subjective, dogmatic or critical, intuitional or rational, scholastic or skeptical, traditional or radical, lead, if rightly followed out, to the same results; but the perfect method is a combination of them all.

The Aristotelian-Platonic, Alberto-Thomistic, Vedanta, and Post-Kantian (Fichte, Schelling, Hegel) philosophies are of special value, on account of their fullness of content, and as representing the final outcome of the cycles of constructive philosophical activity of which they are severally the terms; and the same is true of the Spencerian philosophy, as a rationalized synthesis of empirical natural science.

The true field of philosophy is coextensive with that of actual or possible human thought. Philosophy is the science of first principles and ultimate purposes, of causes, essences and relations; it is the theory of the universe, the rational explanation of the Cosmos, including all history and all thought.

Pure philosophy deals with abstract principles and their Source; applied philosophy is an application of these to the explanation of special groups or kinds of existences, phenomena or activities.

The Absolute is pure, necessary and eternally self-positing Being, infinite, unchangeable, impartite, and of incommunicable substance, as described by Aristotle, Aquinas and Sankaracarya, and is a personal God, in the sense that Knowledge and Bliss, and therefore, Consciousness, are inseparable from perfect Being. As the Object of contemplation He is Beauty, Truth and Goodness; as the Subject of (free, eternal and interiorly non-differentiated) action in relation to actual or possible existence ad extra, He is Power, Wisdom and Love. To each of these predicates corresponds a branch of pure or formal philosophy.

The universe is the finite manifestation and free communication (by an Act eternal in Itself but temporal in Its term) of the Divine Perfections; all that it is and contains, in all its parts, flows from, and is constantly dependent upon, Him (cf. Gioberti and Brownson) and is what and as it is because of Eternal Reasons in the Divine Essence.

The universe pre-exists eternally in the Divine Idea (Logos=God as Self-Object or Knowledge); its final cause is the Divine Will or Love (Holy Spirit=God as Subject-Object, Self-Complacency or Bliss) and derives its contingent and relative existence by participation from (not of ) the Divine Being (The Father= God as Self-Subject).

All created existences, in themselves considered, apart from God, in which manner they do not exist, are nothingness, nescience and evil (Aquinas and Sankaracarya); but as actually existent, and as an ideal exhibition of the Divine Perfections (differentiated by diverse limitations) they share with God in the transcendental predicates of beauty, truth and goodness. Everything is beautiful, true and good, insofar as it has being, and otherwise, only so far as it partakes of nonbeing, that is to say, is deficient in being.

The Eternal Reasons constituting the Divine Idea are reflected in the celestial intelligences or pure spirits (angels) as innate intelligible species (ideas), and in matter as seminal reasons (Aristotle, Aquinas and Scotus).

In individual existences they are represented by the substantial form or active constitutive principle (which becomes in plants and animals the vital and sensitive principle, and in man the spiritual principle or rational soul), and superimposed accidental forms (as of shape, color, etc.); and in the human intellect they become spiritual forms, intelligible species or ideas.

The Divine Idea as actually or potentially reflected in the universe, and constituting its normal or ideal Order, is the (nonsubstantial and impersonal) Over-soul, and the whole body of subordinate ideas contained in it, as governing any particular part or epoch of cosmic or human existence, constitute the special Over-soul of the part or epoch.

The evolution of the corporeal universe represents the more and more perfect realization of the Divine Idea on the finite plane; and human history is a continuation of the same evolution so far, and so far only, as man freely co-operates with (or refrains from acting counter to) the Divine Purposes, and realizes in himself and his works the Divine Idea.

All the aberrations of created wills are in some way and time overruled by, and made to contribute in a special manner to, the Universal Order, which crushes, subjugates and eliminates all obstinately inordinate elements.

Every portion of the Universe is a manifestation and revelation of the Divine Perfections—an epitome of the whole; but this is especially true of the human soul, so that man is, in a special sense, the image of God, and the whole history and philosophy of the universe can be ascertained (cf. Fichte), in its main outlines, by a critical study of his interior operations.

An acknowledgement of the essential trustworthiness, or verity, of Nature, and of human nature, is necessary, under pain of intellectual suicide (cf. Jacobi and the Scottish School); for unless the universal instincts of mankind (which attribute, for example, objective validity and independent reality alike to the data of consciousness and sense, and the categories of the understanding) are true, then no confidence can be placed in any form of intuition or ratiocination.

Sensual and rational intuition are the foundations and sources of all knowledge; the illative faculty (compare Kant’s “pure reason”) recognizes and appropriates all things as true, the aesthetic faculty (cf. judgment”) as beautiful, and the moral faculty (cf. “practical reason”) as good.

The soul being absolutely simple in its essence, these represent simply its diverse aspects or powers. The will, in its highest sense, is simply the activity of thought, i.e., the rational appetite (tendency toward the Good, as such), super-imposed upon the sensitive appetite or Nature-will (tendency toward the good in its particular manifestations, Plato and Aquinas, cf. Schopenhauer) common to man and other animals and, in a less perfect (unconscious, cf. Hartmann) form, even to plants and inorganic substances, in which it reflects the Divine Bliss, as the form reflects the Divine Knowledge and the matter the Divine Being.

The function of the discursive reason is, by analysis and synthesis, to eliminate error from the sensual and ideal data intuitionally given (thesis), and also to bring to light the truths latent in them.

Every possible idea contains some truth, and therefore, every pleasing idea should be accepted, unless some good reason appears for rejecting it. Every possible abstract proposition is true in some sense and false in some sense (cf. Jain logic); and no truth is fully possessed until the opposite doctrine has been analyzed and its positive elements appropriated.

All matter is united to some formative principle or soul. In the case of corporeal substance (excluding non-atomic matter) it is this formative principle which determines the arrangement and habitual motions of the molecules and atoms; the ultimate atoms being ethereal vortices (Sir William Thompson), occupying space, but being incapable of actual division, which, if it should take place, would reduce them to quiescence in the state of non-atomic matter (interstellar ether).

All the phenomena of the corporeal universe are capable of being reduced to mathematical formulae; the universe in this sense being, in accordance with the doctrines of the Samian School), woven out of numbers; the totality of these numerical relations representing the physical over-soul.

The process of evolution is a transition to higher and more numerous forms (heterogeneity) and the subordination of lower forms to higher (integration). The highest forms in the corporeal universe are sociological organisms (to which individual human beings occupy a relation analogous to that of the cells to the animal body), which are subject to the same laws as biological organisms plus the laws governing the free activity of the human will, which are themselves analogues of natural laws.

The ideal end of natural and terrestrial evolution is the complete reconstruction of the Divine Idea in the human intellect, and the perfect realization of the Order (embodiment of the Over-soul) of human society. This end cannot be absolutely reached, but only perpetually approximated to (cf. Fichte).

The end of cosmic evolution (to which the Supernatural Order arising from the Incarnation is a necessary and sufficient means) is the supernatural union of human souls with God, who becomes (in the Beatific Vision) the direct Object of contemplation to the intellect, as its supreme Intelligible Species, in and through which all things are known, the Divine Archetypal Idea thus being possessed at last in the possession of Divinity Itself; and the universe, as Idea in the human intellect, thus returning to its Source.

In the Grand Consummation (Ragnarok, Pralaya, Day of Judgement) all spirits will be united into a perfect Commonwealth, in which the ideal Social Order will be finally attained; and the corporeal universe itself will be gloriously transformed by its reduction into perfect docility and transparency to spirit, through and in which it will return to God, while gaining by that return its own ultimate splendor and perfection.

Merwin-Marie Snell, Mind Magazine, February 1904